LAST DROP

On the night after the accident, I was tormented by fever dreams.

It felt as if I were floating between two worlds, while a darker shadow of mine tried with all its might to hold back the lighter one.

It generated fear of the unknown in an extremely manipulative, insidious way.

There were no words or images, only feelings that eventually convinced the other that change is dangerous.

Nothing is more dangerous.

When I considered the possibility that I might have suffered another lasting injury to the knee that had been operated on barely half a year ago — the one I had worked so hard to restore — I almost collapsed.

I had to wait a few more days for the results, so I could agonize over it in the meantime.

During this period, I could barely put weight on my swollen leg, so I was almost certain that I would once again have to say goodbye to my passion for quite a while.

And in the end, not after all.

The CT showed nothing. By some miracle, I got away with just a few stitches.

There was no popping champagne, no ear-to-ear smile afterward — only a deep realization.

“Okay, I got the message” — maybe that’s something like what I said then.

From that point on, I truly began to feel that I could no longer postpone the change.

No matter how much my ego fought against it, I had to take concrete steps.

But I had no idea how — other than giving up my harmful habits.

Not that it was easy.

Tobacco shop and guilt.

difference.

It was simply hard.

Weakness, addiction, lack of self-discipline — I probably had a bit of all of them.

But an honest intention had started to grow in me, pushing me to ask myself questions.

Why do I feel what I feel?

Where does this immense tension, anxiety, and frequent sadness come from?

How much of it is connected to my parents or my childhood?

And finally: what could be the solution to all this?

If there is one at all…

I spent a lot of time reflecting on these questions during my short retreats, while I cycled long loops around the villages and forest edges near Monor.

I would sit somewhere, and simply think about the root cause of the feelings present in my life

Back then, I had no map, so I was just feeling my way in the dark.

I had no idea about family patterns or how the subconscious mind works — in fact, I didn’t even really know what “the mind” was.

It simply felt good to be alone and practice presence.

Maybe it was an Osho book that inspired me to start meditating — though I could barely hold emptiness for a few seconds amid the flood of incoming mental spam.

For 21 years, every day of my life had been filled with generating unnecessary thoughts.

In all that time, I had been everywhere except the present moment.

After returning to the city from days spent alone, I always felt a bit like an outsider.

I was infected by the sense that everyone wore a mask to hide their true nature.

Among acquaintances, of course, I often voiced my new views after a few beers — earning a few puzzled looks.I began to feel that no one could truly understand what was occupying me at the time.

So I spent that period oscillating between the atmosphere of Budapest and my rural retreats, until the second attempt of my graphic design career began.

I arrived with difficulty.

My enthusiasm showed itself more in skating, while the hours spent at school were something I somehow endured without any real presence.

It went on like this for a while, as anxiety slowly began to reclaim its territory.

At first, it appeared only for a few moments, like a long-lost acquaintance trying to extort attention.

In such moments, that well-known vicious cycle can rebuild itself — the one that quickly triggers the flow of fear of fear.

Not even a month had passed, and I found myself right back where I started.

Of course, this was to be expected.

A separation from my lifestyle was taking place through the universe’s peculiar tools.No matter how much I clung to it, this was already a sinking ship.

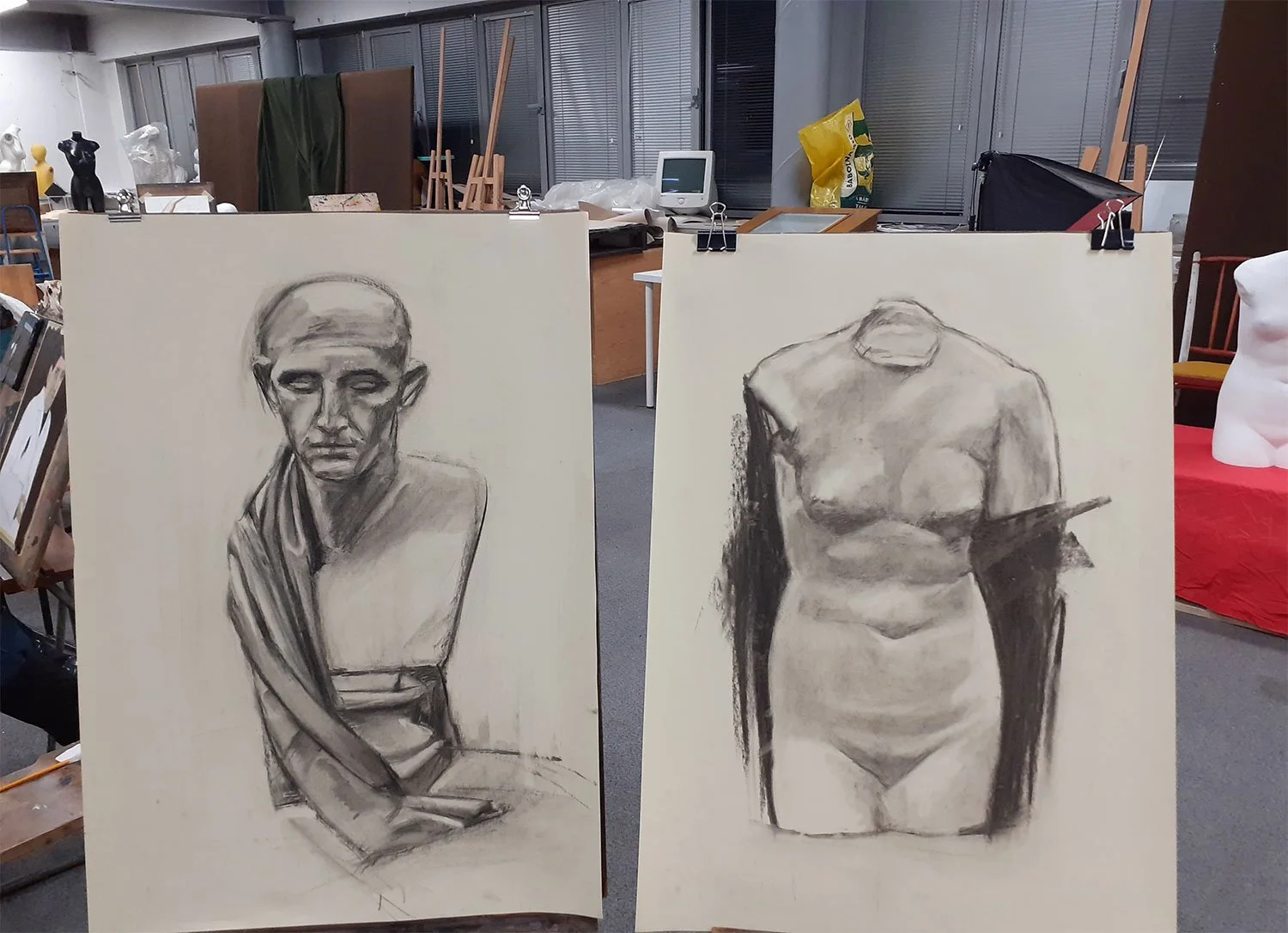

Maybe because of this, I began staying more and more often after school in the empty studio, drawing sculptures and still lifes.

Back then, everyone thought I was doing it out of diligence — when in reality, the only reason was that I could be alone for a while after a whole day of crowd-induced overwhelm.

There was something about that place.

That was the first time I experienced the beneficial effects of art therapy, while I could immerse myself in the basics of observational drawing.

At the same time, another major shift happened.

My mother — with whom I was living at the time — decided to try her luck abroad.

I spent a lot of time thinking about what to do next — and eventually decided to move to Monor, into my grandmother’s family house.

By then, the feeling had ripened in me that I truly wanted this profession.

Graphic design and illustration are paths that don’t end after class — on the contrary, real growth begins at home, and I too needed time for that.

I felt immense gratitude when this opportunity was offered to me, because attending full-time school would have made it extremely challenging to come up with the money for rent every month.

.

Besides all this, there was of course another reason.

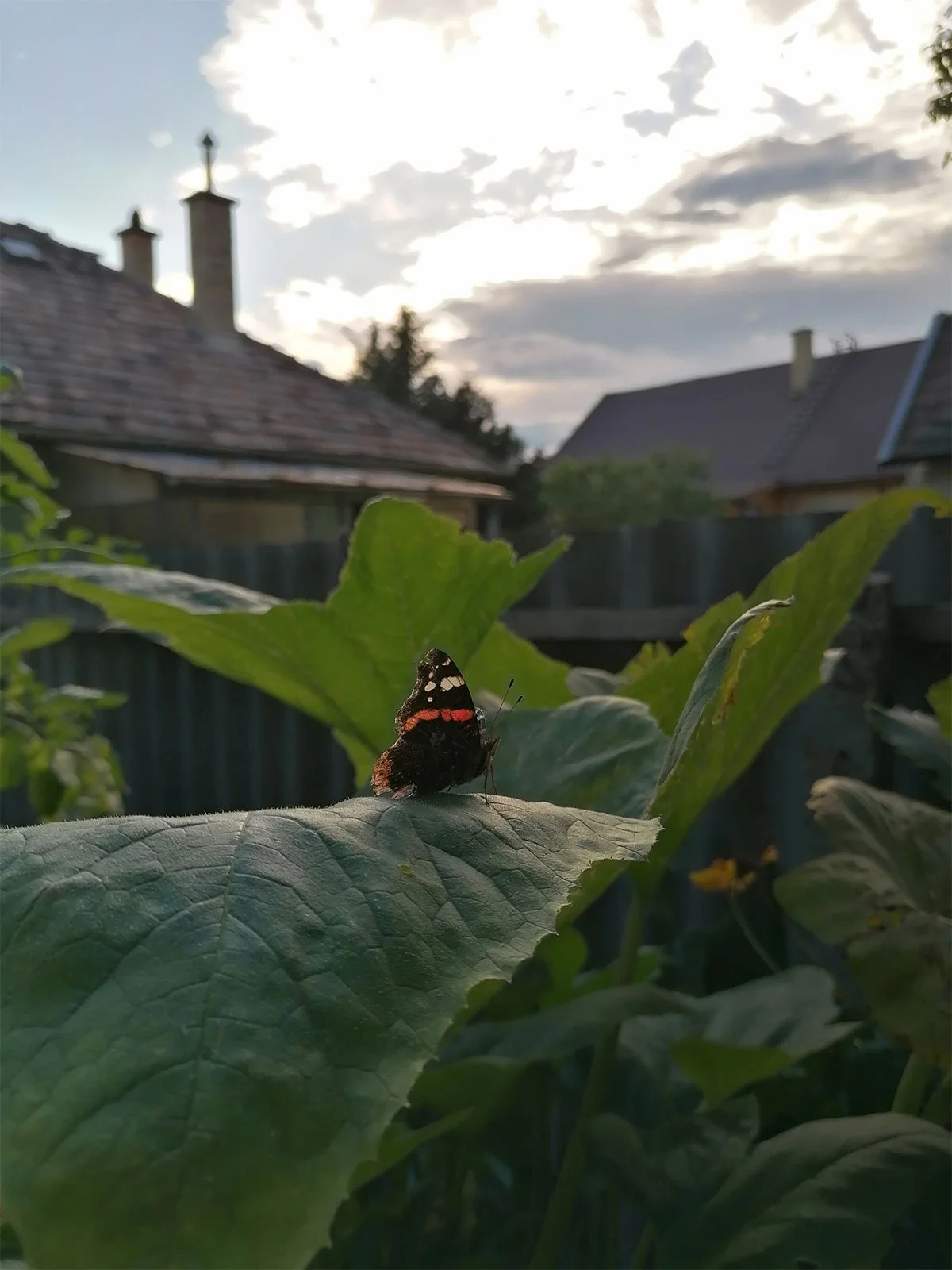

During my summer visits, I had grown fond of that place, and after everything that happened, I felt it would do me good to spend more time in the area.

It was a spacious house with a garden on the outskirts of Monor, close to the forest — a place where I could forget about the outside world for a while whenever I wanted.

It also helped distract me from the addictions I had at the time, which really did start to loosen their grip after a few weeks.

During my time in Budapest, the anxiety had intensified so much that I finally called the doctor and told him, laughing, that he had been right.

Things were starting to get rough again, and I needed a temporary solution — at least something that would help me get to school.

I knew that antidepressants had helped once before — and I also knew that this time I would approach them differently.

He didn’t lecture me.

He simply asked me to hold on and take them for 9–12 months so they could stabilize me.

And, of course, to leave my old lifestyle behind — which was already happening at its own pace anyway.

After this, I spent more and more time alone, whether I was at home or around people.

It felt as if a deeper quality had begun to awaken in me, which my ego of course tried to suppress with all its might — after all, at 21 you’re supposed to have fun, chase girls, and do things like that.

Live — as they say.

Instead, I suddenly stepped into retirement age — or so I thought.

I got pulled into the “grandma hotel.”

Perhaps the final blow was my grandmother’s evening invitations to watch Columbo episodes on Duna TV — which, after the first one, I always politely declined.

Most evenings I oscillated between editing my assignments and smoking cigarettes on the balcony — all while waiting for the anxiety to finally begin to loosen.

This is more or less how the few weeks before the turning point passed — the moment from which everything changed at the root.